Introduction

As you look at the programmes and projects your corporate philanthropy supports, you may find yourself wondering how much impact your gifts truly have. You may wonder if this is the best you can do, or if anything further can be achieved. As you read through the progress reports provided by your staff or grantees, you can quickly surmise what progress has been made, but you are keen to learn more about if, why, how, and how much positive change has or will be created.

Monitoring and evaluation processes will help you to both take stock of what has occurred and optimise what you achieve through your giving. This guide will help inform your process to monitor programme progress and assess results.

Fundamentals

To derive the full value from monitoring progress and assessing results, the monitoring and evaluation processes should be fully integrated throughout each stage of the programme lifecycle. However, all too often they are omitted from the planning stage, completely absent from the implementation phase, and furiously attempted in the final exit stages of a programme.

What is worse is that when organisations do engage in monitoring and evaluation, they do so only to satisfy reporting requirements, rather than seeing it as a tool for improvement.

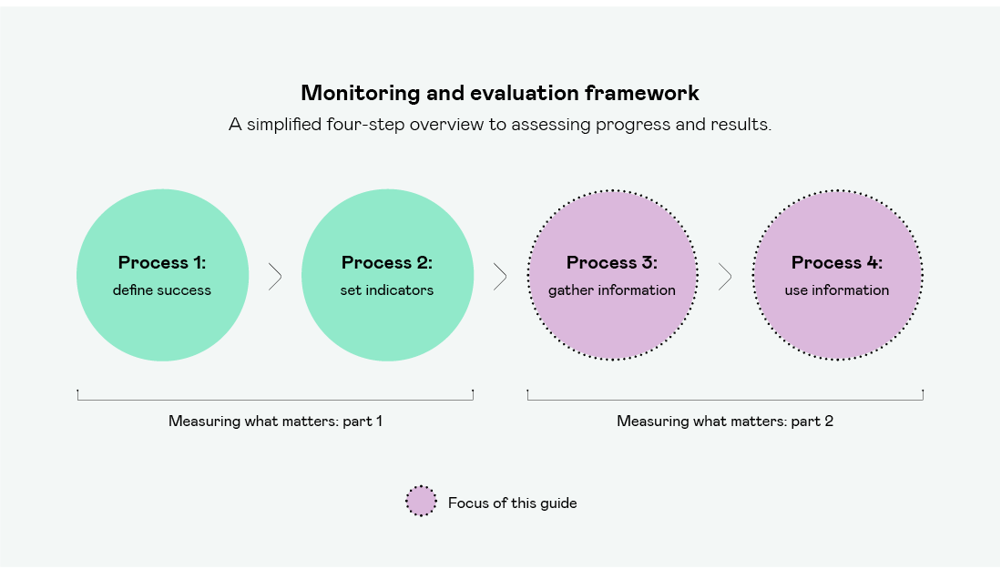

There are four basic processes for monitoring progress and evaluating results. This guide focuses on steps three and four.

1. Define success. Solidifying what a programme is meant to achieve is an initial step that shapes all subsequent monitoring and evaluation processes. Defining success helps to establish the questions a manager or evaluator will seek to answer. Were the inputs sufficient? Was the programme successful? Were the programme participants better off after the programme than they were before? These are all examples of evaluation questions that when investigated, can help improve a programme, showcase successes and challenges, and satisfy the interest of stakeholders.

2. Set indicators, targets, and baselines. Establishing indicators, targets, and baselines is a crucial step in monitoring and measuring implementation progress, results, and longer-term impact. These three elements are invaluable to programme managers as they work to keep a programme on course, isolate issues, exploit successes, and optimise outcomes.

3. Gather information. Access to reliable data and information is a powerful position from which to optimise programme results. Developing a collection plan and gathering information provides the primary evidence base for carefully considered management decisions.

4. Use information. Collecting data is important, but information must actually be utilised to monitor progress, assess results, institute course corrections, and communicate outcomes. Many programmes collect data but never initiate a data- driven feedback loop that can help identify problems and improve results.

Three (poor) reasons to avoid monitoring and evaluation

All too often programmes avoid monitoring and evaluation endeavours. Doing so almost always comes to the detriment of overall outcomes.

1. Financial and capacity constraints. Monitoring and evaluation might feel like a drain on funds, especially when budgets are tight. In an optimal scenario, programmes will be evaluated by external, neutral third parties. However, internally- led monitoring and evaluation undertakings can also be effective if approached objectively – and this option precludes the need to retain dedicated monitoring and evaluation staff. In either case, monitoring and evaluation processes should be built into every phase of the programme lifecycle with responsibilities shared among several individuals involved in each phase.

2. Time constraints. There should not be a trade-off between implementing a programme and monitoring its progress or assessing its results. These two things can be done side-by-side if adequately planned for. There may be cause to delay non-critical monitoring or evaluation processes during crisis situations, but otherwise, they should be accommodated alongside implementation. There are several software packages that can assist with automating data collection and analysis, if time constraints truly exist.

3. Not wanting to be ‘judged’. Monitoring and evaluation is meant to improve, not police programmes. Seeking continuous improvement and optimal results should drive a programme to embrace monitoring and evaluation processes, rather than avoid them for fear of poor results. It is possible that monitoring and evaluation may reveal inadequate progress or results, but more importantly, they can also identify opportunities to reverse the longer-term negative effects of those inadequacies and improve chances for success.

Gather information

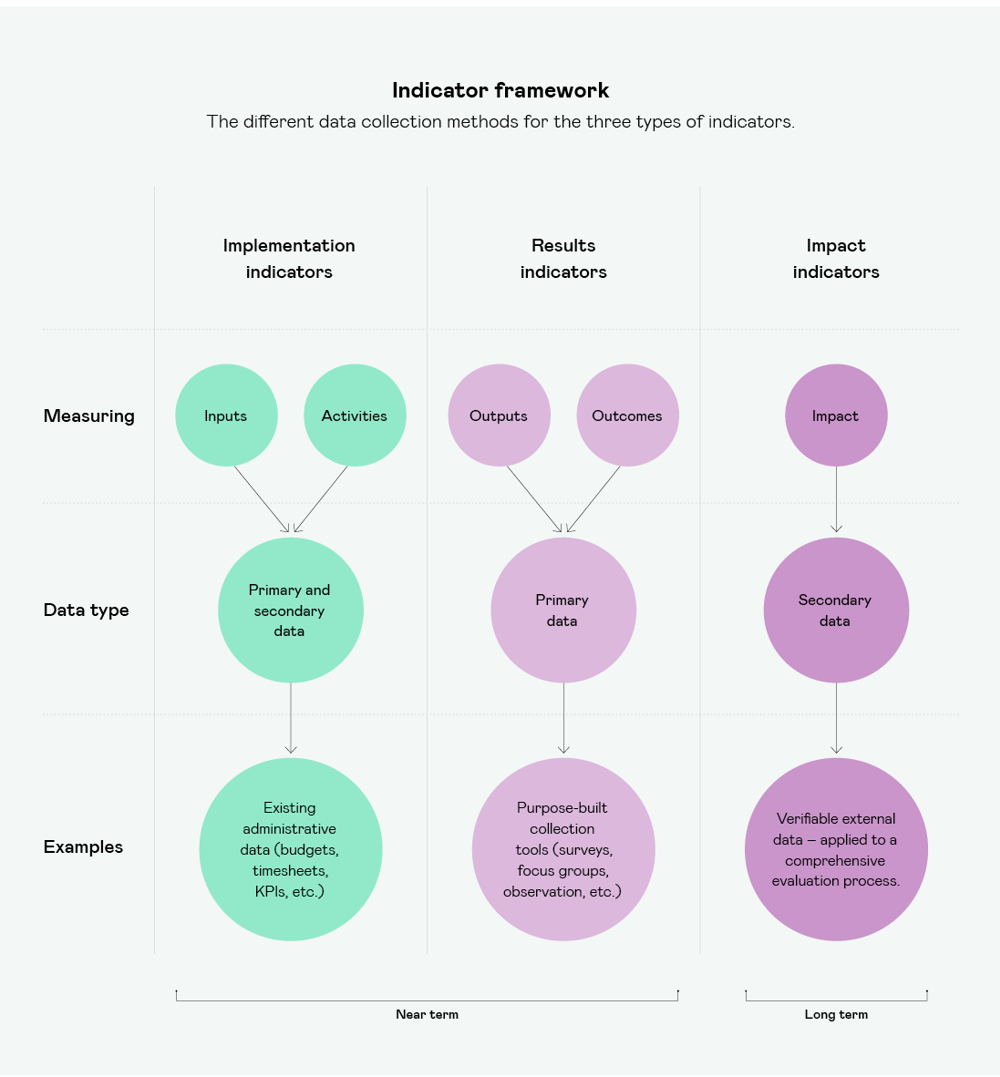

Once indicators, targets, and baselines are set, the next step is to gather information. During this process, programme managers develop and execute a collection plan for gathering data from the various sources outlined in their indicator framework. This information will be used in the near-term to monitor progress and lays the foundation upon which a programme can eventually assess results and impact.

Each of the three types of indicators lends itself to a certain type of data and collection method. Primary data – or data that is newly gathered for a specific intended purpose – is typically collected to measure results indicators. Secondary data, or data originally collected and intended for other objectives but useful elsewhere, is typically employed to measure implementation and impact indicators.

- Implementation indicators measure inputs and activities. Much of this information can be gathered from administrative data including budgets, timesheets, inventories, KPIs, and other information that is collected and monitored for operational purposes. This data is likely already captured in existing systems. Moreover, if an organisation utilises an enterprise resource planning system (ERP), most are pre-configured with a standard performance management component that can track indicators.

If there is no ERP in place, or if a separate monitoring system is preferred, the existing data can be manually extracted from the ERP and plugged into a separate system to suit programmatic monitoring and evaluation purposes. Alternatively, many monitoring and evaluation systems or even performance management software packages designed for commercial enterprise can be configured to seamlessly draw administrative data from existing resource planning systems, thus avoiding the need to manually extract data. - Results indicators measure the outputs of activities or direct outcomes of the overall programme on its beneficiaries. These require purpose-built collection tools such as surveys, observations, focus groups, and longitudinal surveys, which can monitor programmatic effects on participants across several years.

Because primary data collection requires some interaction with beneficiaries or stakeholders, this process has the potential to be labour intensive. Fortunately, there are an increasing number of tools through which to engage more easily. Online surveys, social media platforms, webinar polls, mobile applications and other tools have dramatically improved access to stakeholders and information. - Impact indicators measure the long-term effects of a programme. There are typically many different policies, programmes and agents influencing change in a community and it is difficult to attribute long-term social, economic, environmental or other changes to a specific programme. As a result, impact indicators are the most difficult to collect primary data for, and to evaluate. For example, programmes designed to reduce plastic pollution in the waterways of a community can assess their results by measuring the rubbish removed during the beach clean-up events they organise. But how much impact or influence did the programme have on the total decline in pollution throughout the community?

It is difficult for a programme itself to measure total pollution figures and assess a decline. Further, a recent law limiting the use of plastic bags and bottles certainly would have also influenced the decline in pollution. To help isolate direct impact, programmes can collect verifiable external data to which it can then apply to a more comprehensive evaluation process. In this case, the programme would look to the pollution figures reported by the local environmental agency to measure the decline and aggregate impact of all the actors. It would then apply a qualitative evaluation process to determine its own specific impact.

Gathering data can feel intrusive and be met with resistance either from beneficiaries or from grantees. It is important to create and communicate a shared vision around data as a tool for improvement and not surveillance.

One of the best ways to create that shared vision is to be transparent about what happens with the data once it is collected. Being explicit about the improvements that data will help to promote is a great way to facilitate data collection from a previously hesitant partner or beneficiary.

From the field: can everything be measured?

It is possible to measure most indicators, but it is sometimes impractical to do so. If an indicator is prohibitively expensive or resource intensive to measure, programmes can use proxy indicators or population sampling techniques to gain a ‘directional’ understanding of progress or results. There is nothing wrong with employing a proxy indicator or measuring results for a subset of beneficiaries . Remember, monitoring and evaluation processes are first and foremost tools to help programmes improve. The first obligation is to inform programme changes, so if utilising a proxy indicator or some other method to understand the basic direction or magnitude of changes is robust and reliable enough to inform programme management, then there is no need to invest resources unnecessarily in chasing direct measures.

Use information

Good monitoring and evaluation processes can help to improve programme results, showcase successes or challenges, and satisfy stakeholder needs for information.

To achieve this, a programme must actively utilise the collected data. The sad reality is that far too many programmes do not meaningfully utilise their information to communicate or improve results. After collecting data and measuring indicators, many programmes stop short of implementing the feedback loop that provides insight into the effectiveness of various programmatic levers. Without the feedback loop, programmes cannot isolate useful or problematic areas and are unable to capitalise on what is working, or eliminate what is not.

Evaluations vary in complexity. Assessing results can be as straightforward as measuring results indicators against targets set out for the programme. Or it can be as complex as working to isolate the true programme impact from that of other actors that influence similar outcomes. In either case, qualitative assessments of programme effectiveness can further support these quantitative measures to provide a well-rounded picture of results.

Beyond marking a programme a success or failure, the real benefit to assessing results lies in the ability to utilise assessments to identify areas that can be improved or further exploited.

From the field: do I need to hire an external consultant?

Simplified monitoring and evaluation processes can be intuitive and supported or even managed in-house. However, programme managers tend to be heavily invested in their programmes and can sometimes find it difficult to objectively monitor progress or assess results. Programme evaluations that form the basis of new funding or scaled operations are particularly sensitive to objectivity and benefit from the credibility that a neutral external evaluator brings.

Often a programme is working towards an outcome that is influenced by other factors. For example, a programme working to improve the employability of community youth might face challenges understanding its specific impact when universities, private companies and the government are also offering similar programmes.

Assessments that require in-depth or more complicated evaluations and sophisticated methods may benefit from external expert support. For these cases, or for organisations that feel their staff lack the right skills or capacity, there are many organisations who provide monitoring and evaluation support either for a fee or on a pro-bono basis.

From the field: correcting course

A programme to support community health is interested in evaluating its results. Obesity and diabetes are chronic issues in the community, and the programme has been working for two years to reduce the average body mass index (BMI) of programme participants by five percentage points.

The results reveal that the average reduction in BMI is so far only two percentage points and the programme is falling short of its intended outcomes. But why has the programme fallen short, and can anything be improved? Frustrated that two years of hard work has not yielded the intended results, programme management looks for clues that can help improve the situation.

Because the programme is only two years into operation, management begins an assessment of results indicators to measure programme outcomes. Unsatisfied with the results, the next step is to assess the programme outputs, in this case, participants’ weights and their average daily movement.

Closer inspection of the data reveals that despite an increase in average minutes of daily movement, participant weights have not decreased. In fact, the weight reduction target has been missed by over 50 percent, while the average daily movement indicator has exceeded its target. Management then looks at the implementation indicators, and notices that only 20 percent of participants are enrolled in the healthy meal portion of the programme, versus a 90 percent participation in the exercise classes.

Nutrition management is a key component of weight loss, and this area of the programme is not going according to plan. Going forward, management decides to incentivise programme participants to pair their increased physical activity with healthy meals. They consider offering meals immediately after exercise classes so participants can easily partake. They also survey participants to find out if the current menu is appetising. Any of these actions have the potential to improve programme results and hit the target of reducing BMI by an average of five percentage points.

Results and impact are not necessarily the same thing. Our example evaluates direct results on programme participants, but not necessarily long-term impact in the community. Over the course of several years, the programme defines success as improving overall health across the community. With the right resources and a long-time horizon, programme management may be able to evaluate impact. To do so, it could gather secondary data on the life expectancy of programme participants and compare it with that of other community members who did not participate in the programme.

This complicated experiment might be able to indicate how impactful the programme truly was. Alternatively, the programme may employ proxy indicators to measure impact. Managers might measure rates of heart disease-related deaths, average usage of outdoor cycling paths, or other measures combined with qualitative evidence to approximate if the programme was helpful in curbing poor health and instilling good habits.

Best practice: monitoring progress and assessing results

1. Conduct a readiness assessment. This can highlight organisational gaps that might undermine a programme's ability to carry out all four monitoring and evaluation processes and implement the beneficial feedback loop. Programmes that collect but never use their data likely failed to conduct an assessment that ensures they have the budget, know-how, or mindset to utilise their information.

2. Start early. Monitoring and evaluation should be present in the initial planning phase of a programme or project. Retroactively setting indicators, collecting, and using data only weakens the ability to support improvements and calls evaluation credibility into question.

3. Put aside your ego. Monitoring and evaluation can uncover deficiencies but highlighting gaps and learning from mistakes can be equally as important as succeeding.

4. Share successes and failures. It is wonderful to share successes, but it is also invaluable to share failures. Communicating about challenges helps others benefit from experience without suffering setbacks along the way.

Next steps

Monitoring progress and assessing results will undoubtedly uncover useful lessons that are even more powerful when shared. Taking the time to document and communicate knowledge is invaluable to the community and allows others to benefit from experience without having to suffer the same setbacks. Just as a programme feeds this information back into its operations to improve its own results, consider also offering it externally so that other programmes might do the same.