Introduction

You have defined your giving objectives and set a detailed plan for how you will achieve them. You may have already selected a grantee or partner to help meet your goals. Before you launch, your next priority is to determine what kind of information is needed to measure your programme’s progress, effectiveness or results.

Effective philanthropy, something all corporate givers should strive for, requires more than just a sound strategy and ample resources. To be effective, philanthropy requires a means of monitoring and measuring investments and results.

Indicators are simply pieces of information that objectively suggest that change is occurring. Not to be confused with milestones, indicators are not achievements but rather data points, that when paired with baseline information or a target, can be used to mark where a programme is starting from, where it ends, and to track if it is on course.

Due to the key role they play in determining success, the act of selecting indicators, setting targets, and collecting baseline information for those indicators should form part of the early-stage planning of a philanthropic programme. Failure to do so would be like conducting an exam without first determining the questions, a pass mark, or how participants will be assessed.

Setting suitable indicators is as important as having them in the first place. Creating inappropriate indicators would be like setting a written paper to assess physical fitness. This guide provides an overview of how to identify and define useful programme indicators.

Fundamentals

Before selecting programme indicators, it is helpful to understand the role they play in the larger monitoring and evaluation processes. Though often used interchangeably or consolidated into a single term, monitoring and evaluation are two related but distinct processes, in which indicators serve a crucial function.

Monitoring refers to the tracking and basic assessment of indicators to ensure a programme is on track to meet its targets. Evaluation is a much broader function that not only encompasses monitoring by utilising data from across the lifecycle, but also includes in-depth and comprehensive analysis of additional data and qualitative assessments to determine programme results and impact.

Understanding indicators

Indicators sometimes referred to as ‘metrics’ or ‘markers’, are simply pieces of information that objectively suggest that change is occurring. Indicators aid in several important functions, as outlined below.

- Providing evidence of programme effectiveness

Although effective philanthropy is always the goal, responsible philanthropy requires that programmes at the very least do no harm. Giving programmes should strive to ensure they are achieving their intended goals and avoiding unintended consequences of their work. Indicators provide a means for objectively highlighting programme results – good, bad, or otherwise. Furthermore, measuring and assessing indicators is particularly valuable to long-term programmes that would otherwise wait several years to generate and showcase impact.

- Ensuring implementation occurs as planned or triggering improvements

Indicators can provide reassurance that a programme is on track. They can also act as an early warning signal that something is amiss, creating an opportunity to course correct before challenges become insurmountable. - Laying the groundwork for growth

Early indication of programme effectiveness can earn pilot programmes extra resources for expansion. This evidence base can also serve to attract new public or private sector partners that are more likely to contribute funding or other support once concepts are proven.

From the field: what if there are no indicators?

What would happen if your oven had no thermostat? Or if your car had no fuel gauge? You would likely burn your meal or find yourself walking the final kilometre to your appointment. Indicators are present in everyday life, and in philanthropy, they are invaluable tools to track progress and flag when changes may be needed. Rushing the programme planning phase and omitting indicator selection almost certainly guarantees that a programme cannot be effectively and efficiently managed. It also absolutely guarantees that results will be difficult to assess or to meaningfully communicate.

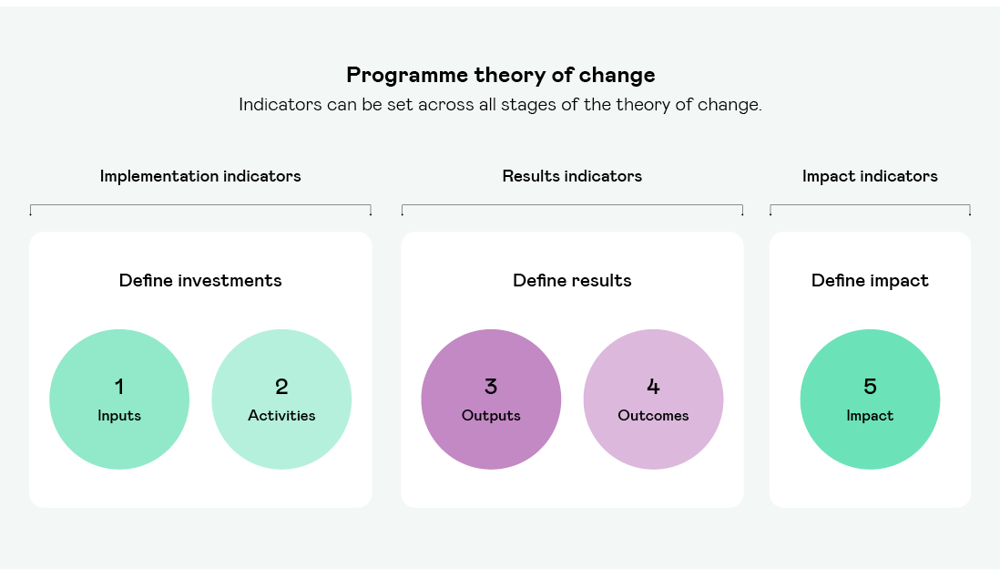

Indicators can be set at varying levels across the programme theory of change. There are three basic types of indicators:

- Impact indicators – these illustrate the long-term effects of a programme on the community or other defined population.

- Results indicators – these relate to programme outcomes and outputs, and illustrate the tangible, near-term achievements of a programme or direct effects on the programme participants or beneficiaries.

- Implementation indicators – these relate to programme activities and inputs, and illustrate the investments dedicated to the programme. Tracking more than simply finances, implementation indicators are particularly helpful in showcasing the total investment in a programme.

From the field: selecting indicators

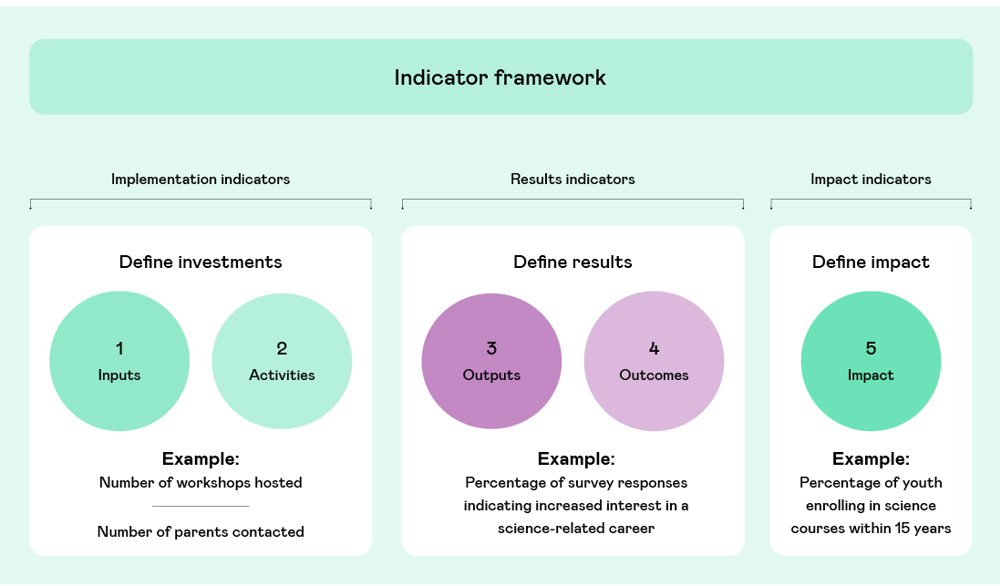

Imagine a programme focused on cultivating an interest in careers in science and technology operates a summer programme for local youth aged 5 to 12. The programme manager might select the following set of indicators across all three levels:

Impact indicators. This programme serves young people aged 5 to 12 by stimulating a passion for science and technology via a summer programme. The theory of change dictates that although the activities do not directly support science careers, students who are introduced to science at an early age are more likely to pursue it in higher education or professionally later in life. Appropriate impact indicators for this programme might include long-term related effects such as the number of participants enrolling in science courses at the local university over the next 4 to 15 years or the number local vacancies for technology jobs within one to two decades.

Results Indicators. Results indicators should be directly linked to the summer programme activities and may include the number of surveyed programme participants responding that they are newly interested in pursuing a science-related career ‘when they grow up’.

Implementation Indicators. Appropriate implementation metrics might include

the number of workshops hosted and the depth of outreach to parents of prospective students

Results and impact indicators

As the majority of corporate giving programmes partner with delivery organisations that manage implementation indicators internally, the remainder of the guide will focus on results and impact indicators.

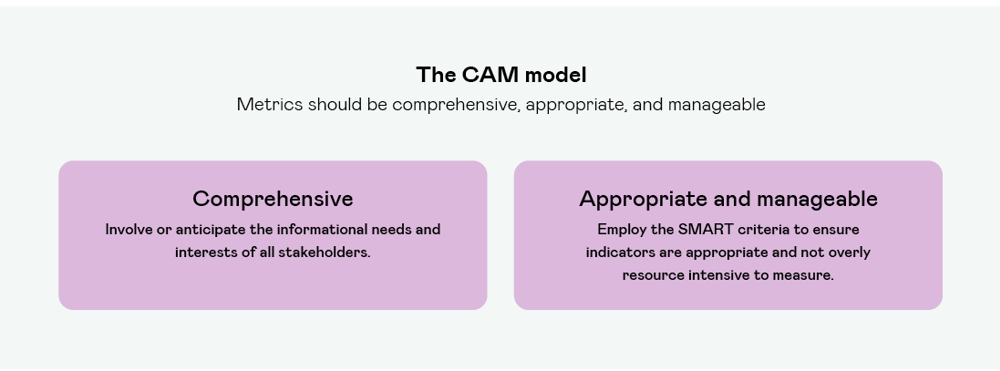

Exploring the CAM model

Indicators are important, but defining the right indicators is equally key to success. Poorly defined indicators can cause real problems for programme management and evaluation. Deficient indicators are often not discovered until well into programme implementation and changing them mid-stream means that time-series data will be disrupted, inconsistent, or unusable. Programmes can avoid this by using the CAM method to define the most comprehensive, appropriate, and manageable metrics for programme impact and results.

- Comprehensive. Results and impact can be best assessed if indicators accurately reflect the informational needs and interests of a wide cast of stakeholders. Unfortunately programmes often only consider their own informational needs, and can fall short in identifying indicators that are relevant to the full spectrum of stakeholders. This leads to evaluation reports that are of little interest to anyone outside the organisation, which can be disastrous for fundraising and partnership expansion down the line. For programmes that are developed and delivered in-house, stakeholders generally include leadership, staff, and programme beneficiaries. For programmes that are delivered through a grantee or other, the list can expand to include the partner’s leadership and staff. For programmes that deliver critical services, or those that are interested in attracting new funding partners or expanding in the future, the list may grow further to include a multitude of external entities including the public and government actors.

- Appropriate and manageable. One should define indicators as rigorously as they would the programme goals.

From the field: identifying stakeholder interests

The board of directors of the firm funding the previously mentioned science and technology programme may consider success to be satisfaction rates amongst the participants and the proportion of repeat users. The student beneficiaries may view success as improvements in their class marks for math and science subjects. Staff may view success as fully attended events and media attention. Indicators must therefore be drawn up to reflect all those different interests, to ensure programme results can be effectively communicated to each stakeholder.

Comprehensive results and impact indicators can be identified by considering what success looks like to each stakeholder. An ideal way to get this information is to involve them in the process. If stakeholders cannot be directly involved in the conversation early on, alternatives include conducting smaller focus groups or to consider success from their unique perspectives and develop a set of indicators to reflect them.

Best practice: involve grantees or beneficiaries in the conversation

Giving programmes are vulnerable to criticism if they do not understand the needs of the individuals or communities they are working to support. The easiest way to mitigate this risk is to involve grantees and beneficiaries early in programme design and indicator selection. Understanding what success looks like to each stakeholder will allow programme staff to effectively manage, measure, and communicate success.

Deploying SMART thinking

Employing SMART parameters to define indicators can help ensure that they not only appropriately reflect programme objectives and are useful in management, but also require only a manageable amount of resources to measure.

- Specific. Indicators should be clearly and precisely defined to ensure accurate and consistent measurement. Programme staff should never have to guess what kind of data they are collecting. For example, an indicator for unemployment should specifically state the unit of measurement, age range, gender, geographical location, and industry type for the population of interest, instead of stating only ‘unemployment’ rates.

- Measurable. Indicators exist to be measured, so it is vital that this is achievable via a reasonable and clear method. Measuring indicators that are dependent on data that is inaccessible or impractical to gather will lead to information gaps, or necessitate additional investment in the collection process. For example, selecting the number of young people who abstain from using drugs as an impact indicator would be incredibly difficult to measure without surveying a large population of young people on a sensitive subject. A better indicator may be the number of young people enrolled in rehabilitation or therapy programmes.

Some results or impact may not be directly measurable. For instance, understanding changes to average incomes for participants in a training programme may be impossible to measure without dependable salary or income data, which is scarce in many scenarios. Instead, you might apply a proxy indicator: access to internet in the home, indoor plumbing, or living in proximity to a hospital could all be considered as proxy indicators for a certain level of wealth.

Administrative data, surveys, observation and other tools and methods can be employed for primary data gathering to measure results indicators. Impact indicators for wider long-term effects can be measured utilising secondary data, or data that has been collected from a verifiable external source. Not every outcome needs to be measured quantitatively. Focus groups, interviews, and other tactics can be employed to measure qualitative outcomes such as judgements or perceptions. In the example of the science programme, student perceptions of their understanding of maths and science could be used as an indicator of programme effectiveness.

It is important to select indicators for data that will ‘move’ within useful timeframes. For example, using student scores on an international literacy exam as an indicator means that the data will only change as often as the test is administered. This is an appropriate indicator as long as programme decisions do not need to be made before the measurement data becomes available, otherwise indicators with data that changes more frequently should be used. - Achievable. Results indicators measure near term, direct and tangible outcomes of a programme while impact indicators measure more long-term effects. It is important to assign indicators that directly and objectively reflect programme effects and that are achievable in the appropriate period for each level of the theory of change. It is easy to get carried away with identifying long-term impact indicators, especially if a programme has many interrelated outcomes. Indicators should be restricted to those that have a causal or correlation link with the programme activities.

- Relevant and reliable. Indicator data is regularly employed to make decisions throughout the life of a programme, so it is important that selected indicators offer relevant and reliable insights. If an indicator cannot be used to make programmatic decisions, or if its reliability is in question, then it is not an appropriate use of resources to measure it.

- Time bound. To support accurate and consistent measurement, indicators should include a definitive period so that periodic measurement comparisons are meaningful. They should also be able to be measured within a realistic timeframe. Finally, the frequency with which each indicator will be measured, and the source of data should be codified when the indicator is. This will ensure information is consistently measured over time.

Best practice: common pitfalls to avoid when selecting indicators

Setting too many or too few indicators

Setting too many indicators requires significant resources dedicated to collecting data. Alternatively, setting too few indicators could lead to information gaps. Only select indicators that will be used in programme management or decision making.

Measuring too frequently or too infrequently

Appropriately setting the frequency for which each indicator is measured can help avoid wasting time and resources. by collecting changes in data that are either too small or large to be useful.

Collecting only quantitative data

Quantitative data can be easier to collect, interpret, and measure, but qualitative data supports a richer, well-rounded programme evaluation, providing insight that numbers alone can’t always offer.

Starting too late

Waiting too long to select or measure indicators results in a loss of opportunity to collect and use valuable data. It also weakens the credibility of the evaluation.

Not using the data

Many programmes fail to collect data, or worse, collect data that is never actually utilised. Indicators, while requiring some effort to measure and assess, provide crucial information that can enhance a programme – but only if it is used. Programmes do not need to reinvent the wheel when it comes to defining indicators; a number of external ‘indicator banks’ exist to provide commonly used metrics across issue areas.

Next steps

Once indicators are selected, it is then necessary to establish a ‘baseline’. Baseline information provides a starting point against which change can be observed through frequent measurement. After the baseline is established, SMART targets can then be established in a similar fashion to any goal-setting exercise.

Once the process is complete, staff will have a complete indicator framework to serve as a powerful management tool throughout the life of the programme.