Introduction

Do you feel that your newsfeed highlights catastrophic events more so now than it did years just a few years ago? You are not alone. Humanitarian crises are growing in number due to an increase in climate-change related weather events, more armed conflict, and other economic shocks triggering mass migration.

In absolute dollar terms, disaster-related philanthropy accounts for a small proportion of overall corporate giving. when compared to other cause areas, such as education, economic development, and healthcare. However, due to increases in the severity and frequency of humanitarian crises, the median dollar value of disaster-related giving grew by 69 percent between 2016 to 2018, outstripping the growth of any other giving category. Corporate giving tends to focus on alleviating the effects of natural disasters, such as storms and flooding, with less institutional funding going towards humanitarian situations such armed conflicts.

In a crisis, corporate philanthropy can help to fill gaps in government response and can be a critical lifeline for civil society organisations working on the front lines. While disaster philanthropy is by its very nature unplanned, engaging in it need not derail your long-term giving strategy. In fact, when done well, it can bolster the meaningful impact of your entire portfolio.

Fundamentals

Grant timeline during a disaster

Half of all of disaster philanthropy occurs during the first four weeks of a crisis, and 70 percent within two months. After six months, giving tends to dry up as the situation falls off the news agenda and off the radar of the donor community. Although initial giving during a catastrophe should be conducted quickly and with a sense of urgency, corporate givers should also bear in mind that disaster recovery is a long game, and the later stages also requires attention and support. Corporate givers should consider a timed-release giving strategy that not only offers support early on in the disaster, but continues to release support throughout the recovery period.

Large-scale disasters have far-reaching and systemic consequences that are

not always apparent for several weeks, or even months. For example, floods and storms may create protracted homelessness, which can lead to school truancy, stresses on mental health and forced migration. Health crises, meanwhile, such as epidemics and pandemics, often can come in waves, with the second and third iterations sometimes proving more taxing than the first.

When jobs and livelihoods are lost, this can lead to economic decline that can be hard to reverse. It can take even longer to remedy the social fallout from crises, such as increased household violence, lower female labour force participation, and the adoption of negative coping methods, such as drug and alcohol abuse.

Despite the great need for post-crisis support, in 2019 just 3 percent of corporate- funded disaster philanthropy was dedicated to recovery efforts4.. Much like stopping a course of antibiotics early, prematurely ending funding can cripple recovery and exacerbate growing social challenges. Corporate givers can avoid this by better partitioning disaster relief to be released across the short and long term.

Grant management during a disaster

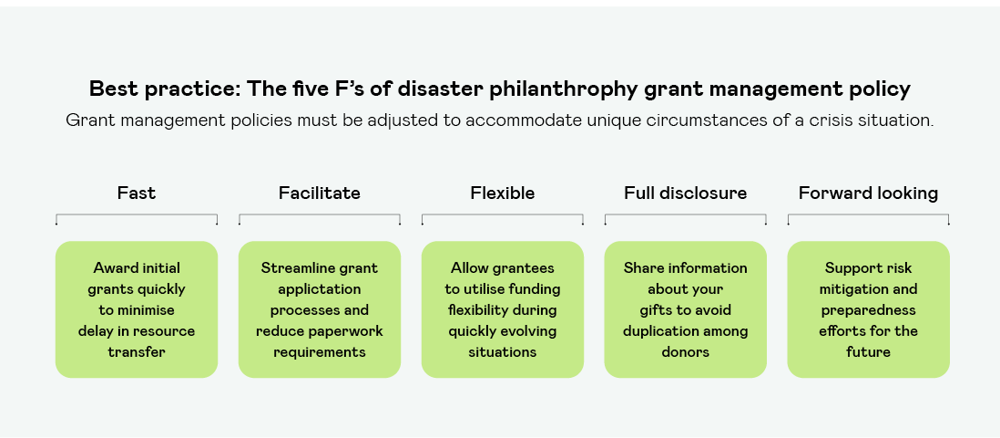

Crises are hard to predict, and can create significant overnight need. For this reason, disaster funding policies may differ from normal practices. Corporate givers should bear in mind the five F’s of best-in-class disaster-response grant management policy:

- Fast. Award grants quickly to minimise delay in resource transfer.

- Facilitate. Streamline your process for grant applications.

- Flexible. Allow grantees to utilise funding flexibly during quickly evolving situations.

- Full disclosure. Share information about your gifts to avoid duplicated efforts.

- Forward looking. Support risk mitigation and preparedness efforts for the future.

1. Fast.

Grantmaking under normal conditions comprises well-structured scopes of work, robust pools of vetted and qualified applicants, and ample timelines for awards. During a crisis, time is of the essence and quick relief cannot rely on business-as- usual processes with long lead times. To speed up awards, corporate givers should temporarily streamline their internal procedures. A timely process during a crisis

is just as good as an excellent process during normal conditions. Reducing the time and number of individuals who are required to review proposals, or reducing the required quorum of applicants, are simple ways to cut the time to award. The average nonprofit organisation typically holds just three months of cash reserves. In a crisis, demands for their services spike exponentially, while payment for those services drop drastically, taxing their already thin operating capital. Making grants quickly during a disaster helps get much-needed capital to frontline organisations.

2. Facilitate

Under normal conditions, grant applicants supply documentation well in advance of

a selection and due diligence process. It is also common practice to require regular reporting and communication from grantees throughout an award period. During crises however, these requirements detract from valuable staff time that could be otherwise dedicated to disaster response. It is therefore important that grant makers strip down or delay requirements so that community organisations can apply for and manage grants more easily. Facilitating a simplified process allows grantees to divert their time to urgent matters at hand.

This does not mean that due diligence, learning, and reporting requirements should be overlooked, or that quality should be sacrificed, but rather that grantmakers take focus on what is truly essential. Using a matrix to map important and urgent tasks can be a helpful approach. The grantmaker lists all the procedures and requirements involved in its grant process, tags them as being either important or unimportant, and further classifies them as urgent or non-urgent. Important items that are also urgent should be tended to immediately, while items that are important but not urgent can be deferred until after the crisis has lessened. Unimportant items can be removed altogether from disaster-response grantmaking.

For example, an important but not necessarily urgent process, such as surveying beneficiary satisfaction, might take second priority to allow the grantee to carry out urgent and important work such as delivering emergency medical attention to hundreds of community members. Requirements that are important but not urgent can always be addressed later in the grant cycle.

3. Flexible

Restricting grant money for use only on specific programme-related expenses is common during normal conditions, but can be crippling in a crisis. Disaster situations evolve at high speed and require agile responses that can be more easily achieved through flexible funding. This allows grants to be deployed across an organisation, including to cover overheads. If a grant was made for new programming prior to the disaster, flexible funding policies can allow previously-committed funding to be diverted away from its original intention towards a more urgent disaster response.

Cash gifts are the most flexible resource that can be deployed in a crisis. In-kind gifts can create logistical challenges, especially during natural disasters. They can takea long time to reach their destination, and in the interim, needs may have changed, rendering them useless. Moreover, in-kind gifts flooding local markets from overseas can further damage already fragile economies.

Corporate givers regularly sponsor community organisations which, under normal conditions, would receive periodic instalments over the course of a year. If these organisations are also relevant to disaster relief, corporate givers may consider front- loading their annual donations so that the grantee can respond to the disaster in the way it sees fit.

4. Full disclosure

Crisis giving is executed at a furious pace. Without clear information about needs, availability of funds, and transfer of gifts, this well-intended rush may lead to duplication or sub-optimal distribution of efforts and resources. In a worst-case scenario, a critical mass of donor gifts land with a small subset of popular organisations, or funding is disproportionately focused on just a few issue areas, leaving others needs unmet. Sharing information about where funds are flowing ensures gifts are made where they are most needed. Even something as simple as sharing a spreadsheet among donors and collaborators is helpful to ensure financial support is evenly spread among grantees and areas of need.

5. Forward looking

Humanitarian disasters are happening year-on-year, all over the world. Despite this, less than 2 percent of corporate philanthropic spending is allocated to forward- looking activities such as disaster preparedness, risk mitigation, and building resilience.. While governments are obligated to be the first responders, philanthropy can provide support through the full life-cycle of a disaster response.

Supporting forward-looking activities also includes taking time to reflect on internal processes. Dedicating time and effort immediately following a grant cycle to conduct an after-action review is a good way to harness lessons and improve crisis-time grant making.