The Egyptian Food Bank launched in 2006 with the goal of wiping out hunger nationwide. Today, its innovative approach to food relief and tackling the root causes of hunger has spread to 30 countries worldwide.

- Primary philanthropist Moez El Shohdi

- Established EFB was established in 2006; FBRN was established in 2013

- Primary focus Food security

- Geography Egypt and the Arab region

Key learnings

Apply all assets

Invest in areas where you can use your existing expertise and peer networks

Define clear goals

Invest time in the early stages to document and prepare the program for growth

Learn and evolve

Continuously monitor, learn, and evolve as the program grows and circumstances change

Challenging the status quo

Invest in changing behaviors to ensure long-lasting impact

In numbers

15 million

According to the World Food Programme, approximately 15 million Egyptians lack access to enough nutritious food to maintain a healthy life

9,000

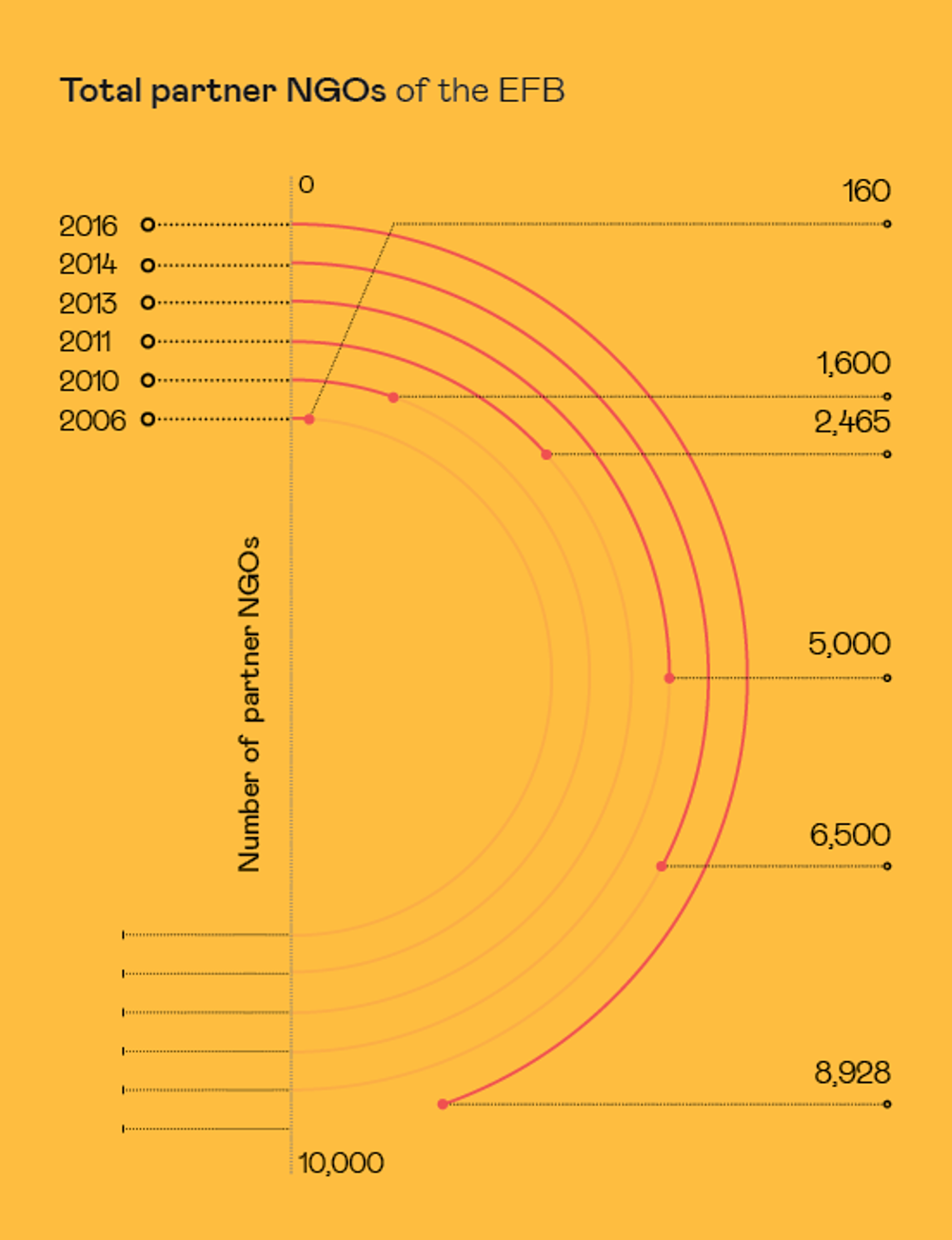

EFB partners with some 9,000 NGOs across Egypt

2030

The year that El Shohdi hopes to end hunger in Egypt

7.3 million

Some 7.3 million former recipients no longer rely on monthly food aid from EFB

The opportunity for impact

In Egypt’s hotels and restaurants, meals served buffet-style are popular. “People build pyramids of food on top of their plates,” says Cairo-based philanthropist Dr Moez El Shohdi, president of the Middle East & Africa division of Style Hotels International. “They only eat 30 to 40 percent of what they take. The rest is wasted.”

The leftovers from a single plate might not seem like much, but they quickly add up. The United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that on average, food loss and waste globally amounts to 30 percent of all food. In the Arab region, 34 percent of food waste occurs during consumption, when uneaten portions are scraped off plates and dumped into the garbage.

El Shohdi has spent his career in the hotel industry. When he watches waiters dispose of all of those portions of food, he finds it doubly disturbing. The trash bins at hotels and restaurants overflow with discarded food, but when he walks out onto the streets in Cairo, he sees many people who are hungry. According to the World Food Programme (WFP), approximately 15 million Egyptians lack access to enough nutritious food to maintain a healthy life.

Hunger imperils not just today’s Egypt, but also tomorrow’s: approximately one out of five young children are chronically malnourished, which leads to stunting — an irreversible condition that prevents children from fully growing, mentally as well as physically. Equally troubling, hunger’s consequences ripple across Egypt’s urban and rural poor. When families struggle to put enough food on the table, children must often forsake school to find work. In Egypt’s poorest regions, 20 percent of children never attend school, fueling a vicious cycle where families remain trapped in poverty and trapped facing hunger.

When Egypt started to suffer an increasing food security crisis in 2005,5 the country lacked food banks to address the growing number of people struggling with hunger. El Shohdi discussed the crisis with a group of friends and relatives. “We said, ‘Why don’t we take the initiative and solve the problem?’” he recalls. Their conclusion: they had the financial resources, business prowess, and networks to help end hunger in Egypt.

Having seen first-hand the excess and the need, El Shohdi and his co-founders concluded it would take a new approach to tackle the dual challenges of food waste and increasing hunger in Egypt.

A bold investment in reducing hunger

El Shohdi and his co-founders envisioned an Egypt where unwanted food is rescued from dinner plates and all families have enough to eat. They wanted to go beyond the standard food bank approach they saw in other countries.

Traditionally, food banks would hand out food to the hungry, meeting an urgent need but not creating permanent solutions to hunger. They would distribute food they received or prepared, but not salvage food that would otherwise go to waste. El Shohdi’s group decided to start a different kind of food bank.

The Egyptian Food Bank (EFB), as they chose to call it, would be distinct in two ways. It would not only respond to immediate hunger by distributing food but also address the root causes of hunger, such as poverty and high unemployment. It would collect excess food from hotels and restaurants, thereby saving food before it went to waste.With this approach, El Shohdi set a bold mission for EFB: to stamp out hunger in Egypt.

In 2006, after meeting regularly to define EFB’s approach and mission, El Shohdi and his 14 co-founders invested US$1.4m of their personal wealth to fund EFB’s first year of operations. During that inaugural year, the founders encouraged hotels and restaurants to reduce food waste and work with selected partner NGOs to redistribute unused food to families in need. El Shohdi, who was vice chairman of the Egyptian Hotel Association at the time, used his network and connections to push hotels and restaurants to commit to the effort. EFB distributed containers for packaging unused food, paid workers for overtime, and gave in-person lessons on reducing food waste.

After seeing the model in action, hotels began to incorporate it in their corporate social responsibility work, by contributing their own funds and engaging employees in the effort.

Having set a clear course of action, the organization grew significantly. A decade later, EFB was serving 12 million individuals annually in Egypt. And a total of 7.3 million former recipients of monthly food no longer rely on such support, thanks to EFB’s development and capacity building services.

To help make EFB financially sustainable, El Shohdi and his co-founders also sought contributions from companies in the region. Today, EFB’s revenues (cash donations, investment returns, and the value of in-kind donations from hotels, restaurants, and corporations) have reached $343m.

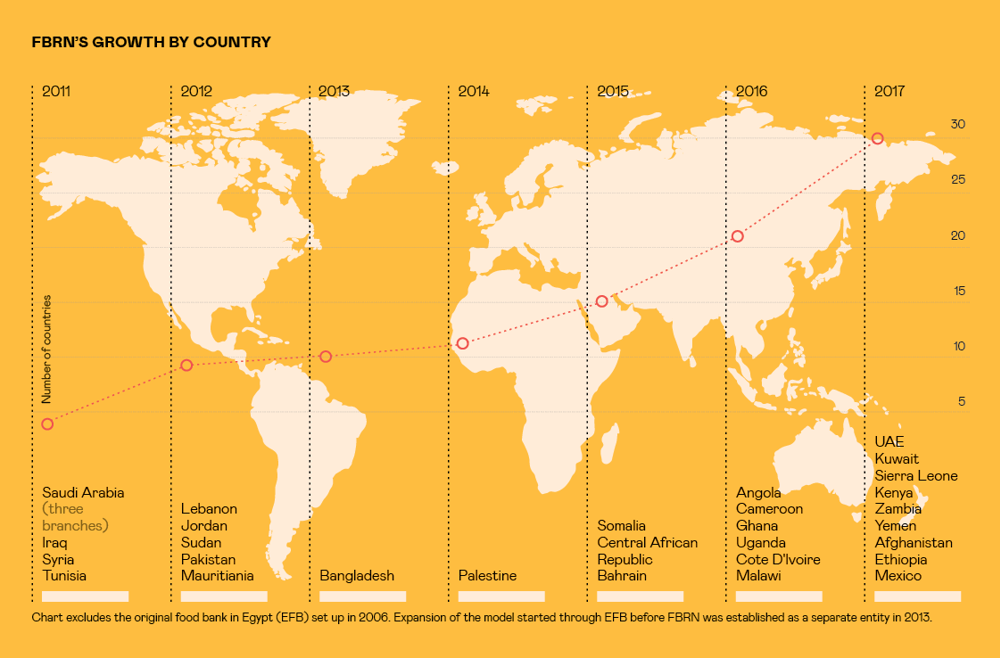

EFB’s success sparked interest in expanding its approach outside of Egypt. In 2010, the United Nations Private Sector Forum invited El Shohdi to present his approach to other countries. In 2013, at the suggestion of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, EFB created a regional network — the Food Banking Regional Network (FBRN) — to export its model to other Arab countries and beyond.

To date, FBRN has helped establish an additional 33 food banks across 30 countries, all using EFB’s model.

How the initiative works

EFB's model rests on six interrelated "pillars" or sets of activities.

1. Feeding programs

The food bank collects donated food, mostly from hotels and restaurants. EFB created a “Wasteless Egypt” app which enables it to contact the nearest partner NGO, which collects the repurposed food. Partner NGOs then distribute the food to individuals and families who are unable to work (the elderly, orphans, female-led households, and those suffering from chronic illness). Hot food is shared with local organizations — such as soup kitchens, schools, hostels, and orphanages — while non-perishables are packaged in boxes and distributed monthly.

2. Development and capacity building programs

Partner NGOs identify unemployed or underemployed people who are capable of working. These individuals receive food in the short term, while the food bank helps develop their skills and matches them to job opportunities. EFB partners with local companies to understand their labor needs: what type of candidates they are looking for and what kind of training is required. The food bank and its partner NGOs then use a common database to select eligible candidates and provide the requisite training.

“In our country, like many countries, education did not serve the needs of the labor market,” says El Shohdi. “We fill the needs of the market.”

For example, one woman and her family, who live in a marginalized community in Cairo, were at risk of going hungry. She became the primary earner for her husband and two children after her husband was diagnosed with cancer. Since 2008, she and her family have received a monthly box of food through the Tanmeyet El Mogtamaa El Mahaly (which translates to ‘local community development’), a partner of the EFB. She has also participated in EFB’s capacity building programs, which give her an opportunity to earn a living.

“The food bank helped me by giving me a machine and fabric, and I was able to begin sewing to earn income,” she recalls.

3. Strengthening partner NGOs’ work

EFB coordinates and strengthens the work of partner NGOs, providing skills training and access to the common database of program participants. It also introduces processes to ensure food donations are used effectively. For example, large amounts of food are donated during Ramadan, resulting in more than enough for one season but a shortfall for the rest of the year.

EFB’s solution is to can and store these donations, particularly meat, and distribute them monthly so families have a consistent source of food.

4. Awareness-building on food waste

EFB’s model depends on reducing food waste and distributing untouched leftovers. This work includes the following activities:

- Creating a “safe food-handling” manual for hotels and restaurants

- Signing a protocol with the Egyptian Hotel Association to save excess untouched food from hotel buffets

- Establishing a food waste penalty in some restaurants and hotels—guests who leave more than a specified amount of food on their plates are charged an additional 50 percent

- Highlighting EFB’s role (such as in reducing food waste) in school textbooks to start educating the next generation.

“We were able to convince the Ministry of Education to include a lesson in the textbooks of students in year three, to study food waste reduction, volunteering, and more. This is how we can change the future,” says El Shohdi.

5. Volunteering programs

The food bank engages families, corporations, universities, and youth volunteers to support its work. Volunteers provide employment training, collect donations for EFB, participate in food packing and distribution, and help conduct quality control visits to NGOs. Currently, EFB has approximately 64,000 volunteers throughout Egypt.

6. Investment to ensure sustainability

To help sustain its operations, the food bank invests in for-profit projects and invests returns back into EFB. For example, EFB has investments in breeding farms, a foil packaging factory, land for agricultural products, and more. While investment income accounts for 15 percent of EFB’s current cash contributions, this segment is growing.

“We asked how we can start to make a more sustainable model for giving. Civic organizations should not depend 100 percent on donations and fundraising,” says El Shohdi.

The food bank regional network helps EFB advance and spread its model across the region. Fidelity to all six pillars is a key component of FBRN’s approach, where each member food bank implements EFB’s model.

“Our pillars work in a complementary sequence. We cannot work on just one of these pillars and leave the others behind or our model does not work,” says FBRN deputy general manager Rasha Nafea.

Within this overall adherence to the pillars, each member food bank has some latitude to prioritize or de-emphasize different pillars to adapt to local contexts. FBRN provides important support to member food banks, particularly during the start-up phase:

Finding members and helping them start operations

To spread the model, FBRN vets and supports organizations (new entities and established food banks) interested in running the program in new countries. It then trains the new FBRN member’s team on how to implement the six pillars and helps it create partnerships with NGOs and corporations.

Maintaining a central database to track metrics

Member food banks and their partner NGOs both use a common database, which tracks the progress of each individual who enters the program. Member food banks follow each participant’s progress against a fixed list of metrics, such as employment status over time. The food banks share these results with the FBRN central office, which monitors the entire network.

Managing corporate partnerships and fundraising

FBRN secures and manages sponsorships from national and multinational companies in the region. These corporate partners — such as Elsewedy Electric, Orascom Development, Etisalat, Pepsi Co, Kellogg’s, Nestle, and Microsoft — donate food and other in-kind contributions (such as employee volunteer time or marketing support), train and hire individuals, and provide direct funding.

Progress and results

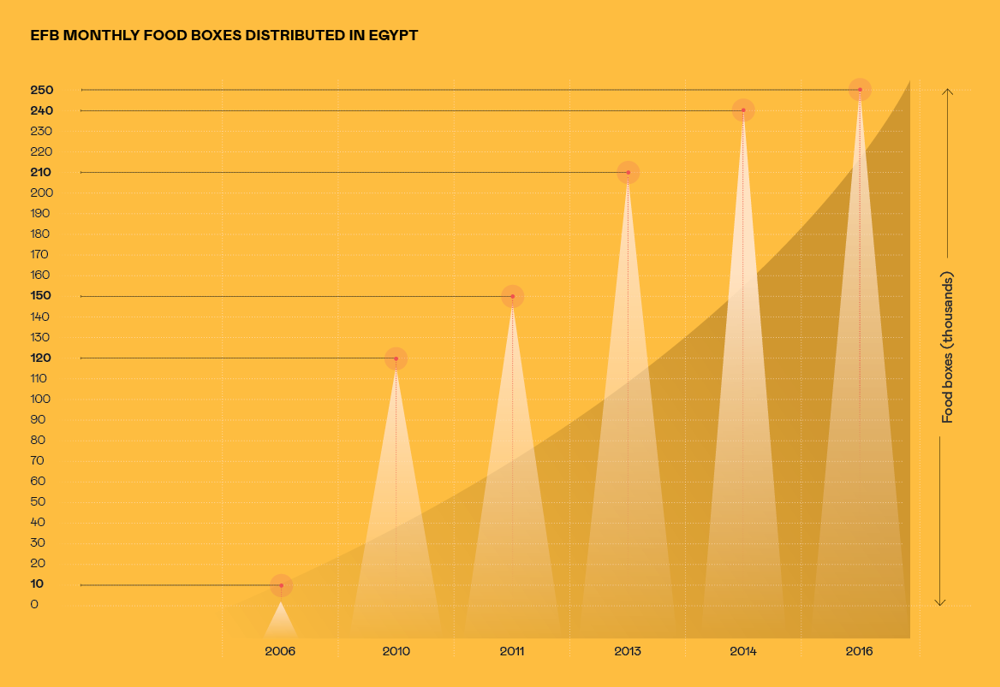

In its first decade, between 2006 and 2016, the Egyptian Food Bank achieved significant results in Egypt. In this time, EFB:

- Reached 12 million individuals annually through EFB’s various feeding and awareness programs, and its training and qualification schemes

- Ensured 7.3 million individuals no longer rely on EFB for monthly food boxes (owing to their participation in EFB’s development and capacity building programs)

- Partnered with 9,000 NGOs across every governorate in Egypt to deliver food and help people build pathways out of hunger

- Saved 20 million meals monthly from being thrown in the garbage in hotels and restaurants

In achieving these results, EFB did have to overcome some hurdles in the early years, including misconceptions about its food delivery model. Some critics complained that the organization gave “used” food to the needy. El Shohdi, his co-founders, and the team realized they needed to put a greater emphasis on informing the public about the issue of food waste and EFB’s approach to responsibly saving and redistributing food. Thus, education became a core part of EFB’s work.

Local realities have also forced El Shohdi to adjust his time horizon. Egypt’s ongoing political and economic instability has made it more challenging for people to climb out of poverty. Between 2005 and 2015, the national poverty rate increased from 20 percent to 27.8 percent.8 Moreover, the tourism industry has declined, meaning that hotels and restaurants have less food to contribute.

“I wanted to end hunger in Egypt by 2020,” El Shohdi says. “But 2011 changed the economy in so many ways, it put us off track. Now I think we can do it by 2030.”

He led the team to reprioritize its investments in order to meet the most pressing need at the time, which was to support the feeding programs. And he continues to develop and modify the specific projects within each pillar to address changing needs.

Expansion efforts beyond Egypt have also made progress. The Food Banking Regional Network now includes 33 members across 30 countries. This expansion has often been demand-driven, with countries expressing interest in adopting the EFB model and FBRN then partnering with them to make it happen.

This growth outside of Egypt has not always been easy. In some countries, FBRN has struggled to identify partners whose values and motivations align with the six-pillar model. Conflict and political instability have been additional challenges, undermining some of FBRN’s first attempts to enter a new country — and necessitating another try.

Understanding how to implement and prioritize the pillars in dramatically different contexts has also been difficult — requiring extra time and, sometimes, a return to funders and sponsors to request a shift in support, for example different types of food donations. This experience, in turn, has helped El Shohdi and his team to learn and to evolve their approach.

FBRN plans to enter South Sudan, Libya, Morocco, Chad, Congo, Mali, Guinea, Djibouti, Oman, Madagascar, Nepal, Zimbabwe, Mauritius, Botswana, Rwanda, Benin, Albania, and Liberia by the end of 2020.

“We are trying to expand to as much of the region as possible — countries in the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia,” says Nafea.

Key learnings

Apply all assets

Invest in areas where you can use your expertise and peer networks

El Shohdi’s deep knowledge of the hotel industry informed the design of EFB’s model. For instance, he knew his experience could help define a realistic approach to reducing food waste. As an industry leader, he could influence standards around food waste management in hotels. El Shohdi dedicated significant time to make this happen. To this day, he taps his business networks for food donations and funding, and to encourage hotels to accept regulatory changes. El Shohdi’s co-founders remain active EFB board members, who use their own networks to raise funds for the organization.

Define clear goals

Invest time in the early stages to document and prepare the program for growth

From the beginning, El Shohdi had his team take the time to document EFB’s programs and processes so that others could replicate them with ease. One of EFB’s first activities in Egypt was to create a manual, “Food Safety Rules in Handling Cooked Foods”. Similarly, FBRN created an operating manual outlining the steps for implementing the six-pillar model, which it uses to train new member food banks.

“FBRN shared many materials with us, which made implementing the program easy,” says Marcella Lembert, who helped bring the FBRN model to Mexico. “We have translated and adapted the manual for hotels and restaurants in Mexico, and since 2014, we have been recovering food from restaurants and hotels across several cities.”

Learn and evolve

Continuously monitor, learn, and evolve as the program grows and circumstances change

El Shohdi felt it was important to run EFB like a business, with a data-informed approach. He set up EFB to track outcomes and refine the model as needed. For example, all partner NGOs use the same database to track individuals, which allows EFB to capture results and ensure the model addresses local needs. Outcome data helps FBRN monitor progress across the 33 food banks.

Of course, local contexts evolve over time, and the food banks must respond. FBRN food banks in Jordan and Lebanon originally emphasized the capacity building programs that focused on skill development and matching candidates to the right employment opportunities. Because these countries have recently experienced an influx of refugees, the top priority has shifted to feeding the hungry.

Challenge the status quo

Invest in changing behaviors to ensure long-lasting impact

For EFB to create sustainable solutions to hunger, El Shohdi learned they needed to invest in changing mindsets and behaviors. EFB is also educating consumers about the role they can play in reducing food waste by not taking more than they can eat.

Additionally, EFB is helping hotels and restaurants realize that untouched leftover food is a resource, not a waste. El Shohdi was surprised, during EFB’s first few years, by how quickly hotels altered their practices and allied with the food bank’s efforts.

“At first we were compensating hotel workers for the time they spent packaging and delivering food to NGOs,” he recalls. “Within a few months, the hotels said, ‘Send us the invoice for the containers, and let us cover their overtime.’ We began changing the mentality. It became part of their CSR.”

By changing mindsets of consumers and suppliers, as well as the behaviors of those in need, EFB just might increase the likelihood that its approach will have a long-term impact on food management and consumption.

About the philanthropist: Moez El Shohdi

Dr Moez El Shohdi is the president, Middle East & Africa, for Style Hotels International. He has been the chairman and CEO of Style Image Management, a hotel and real estate company, for the past decade. With more than 30 years of experience in hotel management, El Shohdi won the Sheraton President’s Award in 1983 and the “Award of International Public Opinion” in 1992. He is also a member of the Egyptian Hotel Association and served on the cabinet’s Tourism Consulting Committee in Egypt.

El Shohdi holds a Bachelor of Commerce degree in Business Administration and Accounting from Cairo University. He also has an MBA, a Master’s degree in International Arbitration, and a PhD in Hotel Management from Cairo University.

This content was first published in 2020 by Project Inspired, a collection of video interviews and case studies drawn from conversations with some of the Arab region’s leading philanthropists and foundations. Project Inspired is supported by the Abdulla Al Ghurair Foundation for Education and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and produced by knowledge partners The Bridgespan Group and Philanthropy Age.